I want my son to learn to be lazy

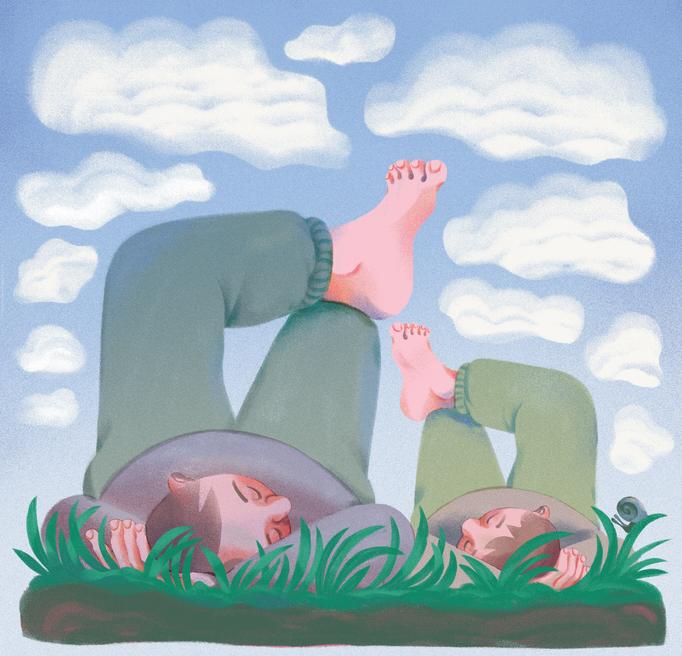

He sees me take a nap every day and wants to do the same. We build elaborate nests and look out the window together, propped up sumptuously on huge piles of pillows. Most of the 3-year-olds I know are loath to go to bed at night, but we snuggle under the covers on cold winter evenings, sighing with synchronized delight.

In 2022, America is a tiring place to live. Almost everyone I know is tired. We're tired of answering work emails after dinner; we are tired of caring for elderly relatives in a crumbling senior care system; worrying about a mass shooting at our children's schools; we are tired of unprocessed pain and untreated illnesses and depressions; we are tired of wildfires becoming commonplace in the west, of flooding and hurricanes ravaging the south and east; we are pretty tired of this endless pandemic. Above all, we are exhausted from trying to carry on as if everything is fine.

More and more people refuse to live with this growing exhaustion: There are 10 million job openings in the United States today, up from 6.4 million before the pandemic.

This trend is led by young people; Millions of people are planning to quit their jobs next year. Some middle-aged people complain about the laziness of today's youth, but as a chronically ill Gen Xer father and rabbi who has spent much of his professional career tending to the dying as his life slows down naturally, I encourage the young people in this Great Renunciation.

I've seen the limits of routine. I want my son to learn to be lazy.

The English word “lazy” derives from the German “laisch”, meaning weak or flimsy, and the Old Norse “lesu”, meaning false or bad. Devon Price, a sociologist who studies laziness, points out that these two origins capture the doublespeak built into the concept.